Any visitor to St. James’s Church in Hamsterley, about 6 miles west of Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham, cannot fail to notice an imposing raised tomb in the churchyard. This is the tomb of ‘William Blackett Esquire of Shull’ (1732-1799) and seven members of his family, including William Stephenson Blackett, who died in Durham gaol in 1840 (he is referred to merely as “William son of the above” on the tombstone). This branch of the family is one of the most interesting and unconventional of all the Blackett lines.

The Blacketts had owned properties in the area for many generations and in the 1756 evidence for the Hamsterley Inclosure Award William is shown as owning Shull, though he continued to occupy Helmington Hall, near Bishop Auckland. The southern boundary of Shull adjoined the Hoppyland estate, which until 1768 belonged to the wealthy Blacketts of Wylam, Northumberland, who were distant cousins of William. William’s family were yeomen, and reasonably well-off, and understandably the inhabitants of Weardale occasionally confused them with the more wealthy branch of the family. In 1772 an announcement in the local newspaper of the marriage of William’s sister Jane (see below) to Lt. Charles Caldwell referred to her as “sister to Sir William Blackett Esq of Helmington”.

No record of a marriage of William has been found. Nevertheless, despite presumably being a respectable member of Weardale society, in his later years he fathered four illegitimate children between 1773 and 1788 by Mary Stephenson, about whom little is known. William and Mary seem to have had some scruples about having (probably) their first illegitimate child, as William Blackett (later known as William Stephenson Blackett or William Blackett Stephenson) was baptised in Chester-le-Street, 16 miles from Hamsterley in 1773. (William senior is stated to be “of Stokesley Hall” and Mary is described as “Mary Blacket”.) However, William’s remaining three children were baptised in Hamsterley. All four were mentioned in his Will, as was Mary Stephenson.

William Stephenson Blackett’s first brush with the law occurred in 1791 when he was charged with destroying “a great number of trees” in the plantations of Anthony Leaton at Hoppyland. William’s motives are not known, but the newspapers reported that he was delivered up to justice by his father for the sake of a reward of ten guineas (£10.50), despite William senior being “a man who is, or has been, possessed of an independent fortune”. (NB. Two years later Hoppyland was destroyed by fire, believed to be arson, though no evidence has been found of William being suspected of any involvement.)

The reference to William senior “having been” possessed of an independent fortune may be significant, implying that his finances had deteriorated. His reasons for selling Helmington in 1792 are unknown, but must have been compelling as Helmington had been owned by his family for more than 100 years. Shull and the neighbouring Shipley comprised a substantial farming estate. In their 1758 report the Commissioners for the Hamsterley Inclosure show the annual value of lands owned by “Mr. William Blackett of Holmindon” (sic) as amounting to £90/4/7 3/4d – (£79/19/7 3/4d freehold and £10/5/- copyhold). This exceeded the value of the lands at Hoppyland owned by “John Blackett Esquire”, the last of the wealthy Blacketts of Wylam to own Hoppyland, which are shown as £89/10/- (£86/10/- freehold and £3 copyhold). East (or High) and West (or Low) Shipley were, however, mortgaged and demised by William in 1767 for a consideration of £650. In addition, in 1772 William Blackett was taken to court to produce an inventory of the goods of the late John Nicholson, his first cousin 1xremoved, of whose estate he was administrator. Five years later the deceased’s uncle sued William to revoke and re-grant the Letters of Administration to the deceased’s estate.

William senior made his Will in 1796, leaving legacies of £1,500 each to his natural (i.e. illegitimate) sons Thomas and John and £1,000 to his natural daughter Ann, all on condition that they attained the age of 21. He also left £20 per year to Mary Stephenson, the mother of his children, and the residue of the estate to his eldest son William Stephenson Blackett. On the death of William senior in 1799 the executors named in the Will (the first of whom was Sir John Eden, himself a descendant of a Blackett, who was a wealthy landowner in the area and an ancestor of Anthony Eden, Prime Minister 1955-1957) renounced Probate, and Letters of Administration with the Will Annexed were granted to William, the eldest son and residuary legatee.

William would have found himself in a difficult position as administrator. His father’s estate, probably largely comprising land, was recorded in the grant of Administration as being between £2,000 and £5,000, a handsome sum but probably insufficient to pay his debts and provide for the legacies totalling £4,000 plus a fund to support the £20 per year to Mary Stephenson, much less leaving anything over for William, the eldest son, as residuary legatee. Thomas became entitled to his legacy of £1500 in 1803, plus a further £1500 when his younger brother John died in 1806 before reaching 21, and Ann, who married John Greenwell in 1801, to her legacy of £1000 in 1804. This is almost certainly why William sold Shull. At his marriage in September 1800 to Frances Marshall, of North Bedburn, William is described as “yeoman”, but by the time of the baptism of their eldest son, William Thomas Blackett in April 1801, William had become a “forgeman“, a profession which all four of his sons subsequently followed. It is possible therefore that Shull was rented out between these two dates, but in December 1801 William is described as “of Shull” at the baptism of his illegitimate son George, whose mother was Margaret Wilson, a single woman of Helmington. (George Wilson was probably conceived at the time that William’s wife was heavily pregnant with their eldest child.) A year previously, on 7 December 1800, William had been described as "of Shull" at the baptism of his illegitimate daughter, Jane Iceton, whose mother was Elizabeth Iceton, a widow. What is known for certain is that William executed a lease and release of Shull, together with allotments on Hamsterley Common on 28 August 1807, followed by an assignment of the lease for 1000 years on 13 January 1809. A purchase price of £2,748/19/- for Shull in 1809 is shown in the ledger of the Backhouse family, now held in the Barclays Bank archives in Manchester.1 It is known that William was living at Chatterley, two miles north-west of Shull, in 1806. (NB. William is said to have established a business in Wolsingham manufacturing shovels and spades. His youngest son, Hugh Marshall Blackett, was running a similar business in Walk Mill Green, Wolsingham in 1871.)

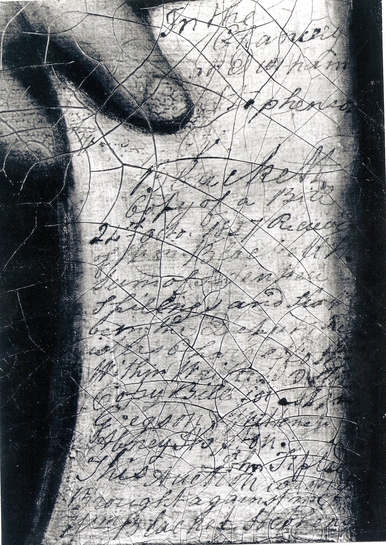

In early 1812 William commenced a prison sentence in Durham gaol, where he was to remain until his death 27 years and 7 months later, three-quarters of which he served as a voluntary inmate. He was committed to prison apparently as a result of a Chancery suit for the non-payment of legal costs and he was certainly in financial difficulties in the years following his father’s death. The Chancery suit seems to have commenced in 1808 when William applied to the court for the return for cancellation of a bond for £316 which he claimed had been obtained from him fraudulently. According to his testimony, in 1806 Benjamin Liddell called at his home in Chatterley demanding payment on a bill of exchange for £150 drawn by William. William was at that time “very much embarrassed in his circumstances”, even though he was seized of freehold estates (Shull?) worth much more than needed to pay all his debts. Liddell therefore threatened to bankrupt him unless William signed a bond for twice the amount of the bill of exchange plus interest, and William, fearful that he would be ruined if he did not comply, duly obliged. It was subsequently held that the bill of exchange was a forgery, but by then William’s bond had been passed on to third parties, who were taking legal action against him for the amount of it. He therefore applied to the Chancery Court for its return.

The defendants’ evidence in the Chancery suit is not known and no further papers concerning the case have been found. However the Chancery Court was notorious for the length of time and excessive costs of its suits. In “Bleak House” Charles Dickens ridicules the snails pace at which Chancery actions proceeded and the crippling expense of them, including the fictitious case of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. It could therefore have been the costs associated with the Chancery case that resulted in William being sent to prison.

He seems to have had a reasonably comfortable time in gaol. He enjoyed conjugal rights and fathered his two youngest children during his incarceration. The elder of these was Elizabeth Wolfe Blackett, born in 1819. Her middle name was probably a tribute to the then prison governor, John Wolfe, or possibly to General James Wolfe, who was killed during the capture of Quebec from the French in 1759. The village of Quebec, 8 miles from Wolsingham, was so named when its fields were enclosed in the year of the general’s death. William would have learned as a child stories of the illustrious general as his Aunt Jane (see 2nd paragraph above) was the sister-in-law of Lt. Col. Henry Caldwell, who served at Quebec under Wolfe and was mentioned in the general’s Will.

William’s youngest son, Hugh Marshall Blackett, was born in 1822 and this prompted William and his wife to have three more of their children belatedly baptised that year, including John Samuel Romilly Blackett, who had been born in 1807. He was presumably named after Sir Samuel Romilly (1757-1818), a chancery barrister who had been appointed chancellor of the county palatine of Durham in 1805, before becoming Solicitor General the following year. He introduced a reform in 1809 whereby prisoners in custody for non-payment of money or costs ordered by the Court of Equity became entitled to a subsistence allowance of 6d per day. This allowance may explain William’s corpulent appearance in the sketch in the 1827 portrait below, perhaps commissioned by William, which is now held at The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, and can be viewed by appointment. (NB. On the back of the portrait is a label stating “William Blackett… Entrance of Durham Jail/Prisoner for debt June 1812/ died in prison January 5th 1840/ Painted by Kinkley…/ a Lawyer… in Durham/ …1878”. It is not clear whether the portrait was painted posthumously or whether the label was added later.)

It may have been William’s relatively benign conditions in gaol that encouraged him to remain there after his formal sentence expired, but by the summer of 1839 his health had deteriorated and his fellow-inmates were complaining at the smell from a putrefying sore on his leg. He died in gaol the following January.

The fortunes of his family ran along differing paths. His brother Thomas, who with his wife is interred in the tomb at Hamsterley, was a farmer, owning 160 acres of land in Low Shipley in 1851. Some of Thomas’s children were reasonably prosperous and one of his grandsons became Rector of Smethcote, Salop. Thomas’s daughter Mary, who is also interred in the tomb, fared less fortunately, marrying in 1874, at the age of 49, Baker Greenwell, a farmer 16 years her junior. By 1881 Baker was unemployed and the couple were living in South Bedburn. Mary died at the end of 1883 and in 1890 Baker married Mary Harling, who must have seemed like a child bride in comparison to his first wife, being a mere five years older than him. (She is described in the 1891 census as “police constable”!)

William Stephenson Blackett’s sister Ann, who had married John Greenwell, moved to the London area some time before 1822 and lived for many years in Bethnal Green. Her descendants seem to have been respectable working people (two grandsons became safe-makers), but her daughter Mary died unmarried in Bethnal Green workhouse in 1894.

![Grave of William Stevenson[sic] Blackett in Hamsterley churchyard](/sites/default/files/inline-images/WSB_gravestone_0.jpeg)

Two of William Stephenson Blackett’s children followed in their grandfather’s unconventional (by the standards of those times) footsteps. Mary Ann Blackett had five illegitimate children between 1823 and 1834, the father of whom is not known. (One of these children, Jane, had an illegitimate daughter, Frances, and another of Mary Ann’s children, Frances, had a son, Thomas, born out of wedlock before she married William Bland.) And Hugh Marshall Blackett had six children by Elizabeth Jane Wheatley, whom he never married, presumably because Hugh’s wife, Mary Ann Lockey, was still living.

The real mystery, however, remains Mary Stephenson and why William Blackett never married her. No record of her baptism, nor of her burial has been found and it is not kown whether she and William were prevented from marrying through one or both of them being married to someone else.

1 We are indebted to John Lavis of Shull for the information on the sale of the property.